Summer seminars focus on Sioux River Valley natives

CHPC working to nominate rock to National Register

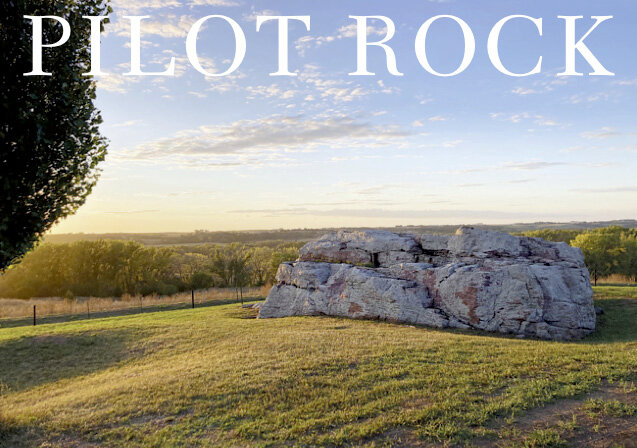

For the first time in almost 175 years, members of the Sioux Nation, the Yanktonai Dakota, returned to Pilot Rock.

Last Friday, members of the Flandreau-Santee Sioux tribe of South Dakota offered insight as to why Pilot Rock is just one part of the region's larger indigenous history.

A few dozen people gathered atop the perch the rock occupies, overlooking the Little Sioux River Valley south of Cherokee to hear their stories.

A plate of food, an offering to their ancestors, can be spotted just inside of the fence separating visitors from the rock. The afternoon sun is tamed by a gentle breeze and the sing-song of birds fills the air.

The event was a stop in a larger summer program, “Summer of the Little Sioux: Following the Inkpaduta Canoe Trail” put on in part by the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Cherokee Historic Preservation Commission and the Sanford Museum.

For centuries, the Dakota people native to the region used the rock as a landmark to know how far they travelled and where they were headed.

Early European settlers moving west used it for the same purpose before eventually establishing the town of Cherokee.

But its significance is still deeply rooted in the Dakota culture.

Much of the Northwest Iowa land once belonged to the Dakota people, Pilot Rock too. But as the federal government pushed for westward expansion in the early 19th century and discovered fertile soil in the Midwest and Great Plains, treaties and land acquisitions took most of it away.

Now, through oral history and initiatives like Makoce Ikikcupi — or Land Recovery in the native Dakota dialect — displaced indigenous groups are working to regain the land that was taken from them.

Native history is American history

As an effort to preserve the monument, the Cherokee Historical Preservation Commission is working to nominate Pilot Rock to the National Park Service’s National Register of Historic Places.

But if Dennis Gill had it his way, he would have the entire plot of land around the Pilot Rock site fenced off and returned to his people.

Gill, a senior member of the Yanktonai Dakota tribe, believes not all of his people’s sites are meant to be seen.

He also believes that identification and preservation of native sites don’t always have the desired outcome.

“Most of the places we identified were destroyed anyway,” he told Friday’s group.

Gill has gone around much of the Midwest to previously Dakota-occupied territories to help archaeologists identify sites and monuments similar to that of Pilot Rock.

He points out the stark contrast between preservation of Native American history and that of the early settlers that colonized their land.

He also brings up the Pike Treaty, signed in 1805 that involved the purchase of land from the Dakota people that occupied nearly 100,000 acres of land near where the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers meet.

“Take away whatever is sacred to them, it will disarm them,” Gill says of the mentality used by settlers and the government to take over native land.

With so much land out of the hands of native people, so many artifacts stolen and graves robbed, Gill believes that is all the more reason to preserve and worship whatever they have left.

He likened it to if a plot at a modern cemetery was dug up and the remains were stolen. That is how the native populations feel when sacred grounds are disturbed.

“The difference is humanity and morality,” he says of the treatment of native peoples versus European settlers. “It was not your land to begin with.”

Gill doesn’t want to bring shame to those of European descent, but instead to bring about a new way of thinking about and approaching native lands.

A member from a Canadian-based branch of the tribe hopes discussions like these will further educate both citizens and North American officials about the hardship faced by native people.

Chief Raymond Brown explained that, to his people, something like Pilot Rock is more than just a stone in the dirt.

Brown also talks about the Creator and why his people believe they were put on the earth.

“The only thing He gave us is this land to protect,” he said. “That’s all we want to do.”